Why Study Educational Psychology?

Citation: Huitt, W. (2019). Why study educational psychology? Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta, GA: Valdosta State University. Retrieved from http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/topics/intro/whyedpsy.html

Return to | EdPsyc Interactive: Courses |

There is some discussion among practicing educators about the importance of studying educational psychology. One way to think about this issue is to define some terms.

Education The process of:

(1) developing the capacities and potential of the individual so as to prepare that individual to be successful in a specific society or culture. From this perspective, education is serving primarily an individual development function.

(2) the process by which society transmits to new members the values, beliefs, knowledge, and symbolic expressions to make communication possible within society. In this sense, education is serving a social and cultural function.

the scientific study of the mind and behavior (or behavior and mental processes), especially as it relates to individual human beings.

The definition of education becomes a little more complicated when one recognizes the three categories of education: informal, non-informal, and formal (Fordham, 1993; LaBelle, 1982). Informal education begins at birth and continues throughout life. It is provided by parents, siblings, friends, and so forth; it is constant and ongoing. Non-formal education involves somewhat structured guidance of learning, but is done without a lot of formal structure. Attending Sunday school or Boy or Girl Scout meetings would involve this category of education.

Formal education, or schooling, generally begins somewhere between 4 and 6 when children are gathered together for the purposes of specific guidance related to skills and competencies that society deems important. In the USA, it generally continues through grade 12 for at least 75% of adolescents and then sporadically throughout adulthood. For most of the twentieth century, once the formal primary or secondary schooling was completed, a person's activity in a formal teaching/learning process was over (Wagner, 2008). However, in today's rapidly changing environment (Huitt, 2017), adults are quite often learning in formal settings throughout their working lives and even into retirement.

Educational Psychology, then, is a combination or overlapping of two separate fields of study. The first is psychology. Note that it is the scientific study of mind or mental processes (covert or internal) as well as behavior (overt or external). People who study psychological phenomena are not necessarily limited to the study of human beings (a large body of research relating to animals has been developed) nor are they limited to only studying individuals. However, when studying groups of individuals, the focus is generally on how individuals perform within the group rather than the study of the group as a whole. Scientists who study animals and people in terms of group- and institutional-behavior generally align themselves with sociology while individuals who focus on human culture and belief systems generally align themselves with anthropology.

The second field of study with which educational psychology aligns itself is education or more specifically schooling, as defined above. That is, the primary focus of this subdiscipline of psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior (or mental processes and behavior) in the context of formally socializing and developing the potential of individual human beings.

Educational psychology is therefore a distinct scientific discipline within psychology that includes both methods of study and a resulting knowledge base. While it is concerned primarily with understanding the processes of teaching and learning that take place within formal environments, it is also concerned with affiliated operations and procedures such as curriculum development, assessment, and evaluation. Educational psychologists are interested in a wide variety of topics such as learning theories; teaching methods; motivation; cognitive, emotional, and moral development; and parent/child relationships.

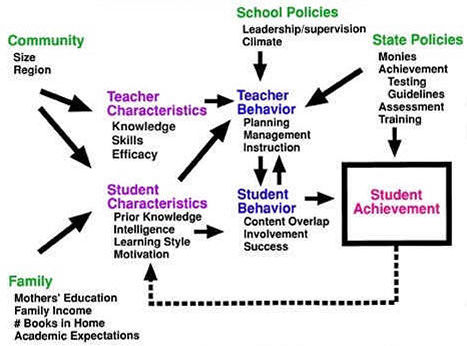

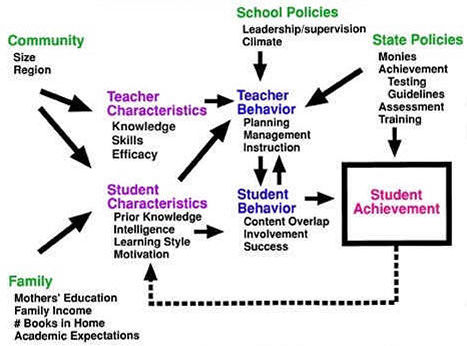

There are a variety of frameworks and models that depict how various factors impact measures of learning completed outside of the classroom (McIlrath & Huitt, 1995). The following is a simple example of how some of these variables might interact (see Figure 1). Context variables such as the size and region of the community impact teacher and student characteristics while the context variables associated with the family impact student characteristics. Of course, there are other important context variables that could also be considered such as the movement from an industrial to a digital and information-based economy. Additional context variables associated with school and state policies, such as mandated standardized testing, combine with teacher and student characteristics to impact teacher behavior. Teacher behavior along with student characteristics influence student behavior, especially those variables associated with Academic Learning Time or the time learners actually spend on important content. Student classroom behavior then influences teacher classroom behavior in an interactive pattern. Student classroom behavior, therefore, is the most direct influence on student achievement as measured by instruments influenced by state policies. Student achievement at the end of one school year then becomes a student characteristic at the beginning of the next. Additional outcome variables that are important for success in the information age, such as emotional development, social development, or self-regulation can be considered in the same manner.

Figure 1. A Model of the Teaching-Learning Process

The actual schooling process is generally described through steps in the curriculum development process. Stephani (2004-05) highlighted the major components of a schooling system in her model of curriculum development (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. A Logical Model of Curriculum Development

Notice that the statement of desired outcomes is at the center of the process and influences all other components. In today’s global, digital age with change occurring at an exponential rate (Huitt, 2017), stating these goals, especially if they are to be relevant for both local and global contexts, is not easy, let alone organizing the other components of the school system so that excellence is attained at all levels (Fullan, 2013; Wagner, 2008).

One aspect of stating desired outcomes for a school system is to identify what is not likely to change as well as what is most likely to change. Educational psychology can be helpful in identifying the former as knowledge of human development is one component of the field. An overview of the potentials for human development should therefore be a feature of establishing desired outcomes (Huitt, 2018a) and is generally the focus of an entire course in an educational psychology program. The task of describing what is likely to change is more complicated. While describing the current conditions for those adults in higher education or the workforce is an ongoing discussion (Diamandis, & Kotler, 2012, 2015), it becomes more difficult for those still in the PreK-12 (primary and secondary) system . For example, learners presenting in high school will leave the system in one to 5 years. Identifying the present circumstances and trends is much easier for this group than for those who are presently in the middle grades who will do so in five to ten years. Likewise, the challenge becomes even more difficult for those presently in elementary or primary school who will enter the workforce and higher education in 10 to 15 years and practically impossible for those presently in PreK and kindergarten who will do so in 15 to 20 years. Just reflect on all the changes that have occurred in the last 10 to 20 years and then imagine how double that amount of change will occur in the next several decades (Kurzweil, 2005). Taking into account what will and will not change over the coming decades, some scholars believe schooling should focus on developing glocal citizens (Huitt, 2018b); that is, individuals who can live anywhere they choose, but are also prepared to participate in, and contribute, to their local communities.

The next component in Stefani’s (2004-05) model is to development means for assessing the desired outcomes. Measurement and evaluation is another component of educational psychology that generally receives attention in a separate course (Darling-Hammond, Wilhoit, & Pittenger, 2014). As parents and educators become more aware of the importance of focusing on the development of the whole child, there is an increased interest in alternative means of assessment beyond those provided by standardized tests (American Educational Research Association, 2000), such as the use of electronic portfolios (see http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/katie/ as an example).

A third component, how human beings learn, is another major component of educational psychology. Learning can be defined as the relatively permanent change in an individual's behavior or behavior potential (or capability) as a result of experience or practice (i.e., an internal change inferred from overt behavior). This can be compared with maturation (biological growth and development), the second primary process producing relatively permanent change. Therefore, when a relatively permanent change occurs in ourselves or others, the primary cause was either maturation (biology) or learning (experience), or, as is often the case, some combination of both.

There are currently eight major theories of learning that are covered in most educational psychology textbooks: behavioral/operant conditioning, cognitive information processing, social learning theory, humanistic, cognitive constructivism, social constructivism, social cognitive theory, and connectionism (Huitt, 2013). Each of these has a primary focus of learning, a set of assumptions that guide the development of research questions, a view of the learner, and a database of basic principles of learning that are derived from research. While most researchers advocate for their particular view of learning, educational practitioners can be more innovative and effective in applying the theories to meet the needs of their particular learners, especially as conditions change rapidly (Darling-Hammond, & Sykes, 2003).

Another component of Stephani’s (2004-5) model is teaching or classroom practice. As educators, there is nothing we can do to alter an individual's biology; the only influence open to us is to provide an opportunity for students to engage in experiences that will lead to relatively permanent change. Teaching, then, can be thought of as the purposeful direction and management of the learning process. Note that teaching is not giving knowledge or skills to students; rather, teaching is the process of providing guided opportunities for students to produce relatively permanent change through their engagement in experiences provided by the teacher.

One way that educational psychology can provide benefit to practicing educators is the development of instructional models, strategies, and methods that are explicitly connected to learning theory. For example, the traditional direct or explicit instruction is based on operant conditioning, cognitive information processing, and social learning theories (Huitt, Monetti, & Hummel, 2009) while constructivism is based more on principles derived from humanism, cognitive and social constructivistic learning theories, as well as social cognitive theory (Tobias & Duffy, 2009). However, newer approaches such as the flipped classroom, when implemented correctly, can incorporate all of the learning theories described above (Huitt & Vernon, 2015).

Additionally, empirical research in educational psychology related to classroom practice can be beneficial. For example, Hattie (as cited in Huitt, Huitt, Monetti, & Hummel, 2009) completed a meta-analysis of over 800 meta-analyses of factors related to student achievement. He identified 138 variables that had an effect size larger than d = 0.39. (Note: An effect size is approximately equal to a standard deviation; this provides an estimate of the strength of the relationship between variables). In one example, Hattie discovered that learners’ self-report of grades was a better predictor of student achievement than the actual measures of prior achievement (d = 1.44 versus d = 0.67, respectively). This supports the contention of social cognitive learning theorists that learners’ self-efficacy beliefs are an important component of school learning (Bandura, 1994). Likewise, Hattie found that learners in Piagetian programs that matched the instructional method to the learners’ Piagetian stage had significantly better student achievement than those who did not (d = 1.28), thereby validating the cognitive constructivistic learning theory (Lutz & Huitt, 2004).

Hattie and Donoghue (2016) continued this meta-analysis of meta-analyses and constructed a model of learning that shows how specific learning strategies impact learning at different stages in the processing of cognitive information issues of motivation, agency, and skill development. Again, this research supports learning theories associated with each of these concepts in the model. If educators truly want to develop human potential for adapting to an exponentially-changing world, there is no better instructional activity than to guide learners to take control of the learning process.

The final component in Stephani’s (2004-05) model is program evaluation and communication of results. Again, this issue is a component of educational psychology, although it is a specialty field that generally is addressed in a specific course (Rossi, Lipsey, & Henry, 2019).

In summary, the primary purpose of schooling, which is only one of the institutional influences in a person's education, is to assist the individual to better develop his or her full potential as well as to develop the knowledge, attitudes, and skills to interact with the environment in a successful manner. The family, religious organizations, and community also share primary responsibility in the educational process. Educational psychology provides important background knowledge that preservice and inservice educators can use as the foundation for professional practice. In combination with information on human growth and development and specific content knowledge, information on theories of learning and instructional practice provide the foundation for classroom and school methods and procedures (Shulman, 1986, 1987; Mishra & Koehler, 2006). What you will study in educational psychology is applicable to a wide variety of content- and age-specific teaching activities.

References

| Internet Resources | Electronic Files | Additional articles | Additional books |

Return to:

All materials on this website [http://www.edpsycinteractive.org] are, unless otherwise stated, the property of William G. Huitt. Copyright and other intellectual property laws protect these materials. Reproduction or retransmission of the materials, in whole or in part, in any manner, without the prior written consent of the copyright holder, is a violation of copyright law.