What Is A Human Being

And Why Is Education Necessary

Source: Huitt, W. (2019, May). What is a human being and why is education necessary (revised). Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta State University. http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/topics/intro/human.html

Return to: | Brilliant Star Framework | Home |

Countries around the world are seeking ways to better prepare their children and youth for successful adulthood in the twenty-first century (Smith & Day, 1990; Jakobi & Teltemann, 2011). Unfortunately, there is no easy, readily available solution to this challenge. One reason is that the alternatives that one considers depends on the worldview and/or paradigm one uses to describe a human being and the value of education (Huitt, 2018b). Therefore, discussion of alternatives is often an implicit discussion of worldviews and paradigms. For example, if one adopts a secular/materialistic worldview, one sees a human being in strictly materialistic terms whereas if one adopts a cosmic-spiritual worldview one would propose that there is some part of the human being that survives physical death. And if one adopts a God-centered worldview one would likely look to a set of scriptures or traditions to define a human being and a life after an earthly existence. Holders of each of these alternative worldviews will develop somewhat different alternatives and establish different criteria for choosing among them.

Likewise, one's paradigm can influence how one interprets reality and organizes facts, concepts, and principles (Huitt, 2011b). For example, if one were to adopt a mechanistic or reductionistic paradigm, one would look at formal education as a separate entity and investigate how the structure and functions of teachers and schools would impact human development (eg, Hattie, 2009; Squires et al., 1982). However, if one adopts an existential/phenomenological paradigm one would look at human perceptions and interpretations of schooling (Rogers, & Freiberg, 1994). And if one were to adopt an organismic/systems paradigm one would seek to describe the whole person embedded in multiple layers of context or environment (Huitt, 2012).

More often than not, the alternative policy makers select presently is a materialistic/mechanistic worldview/paradigm combination with a focus on students' attaining high levels of academic achievement (Postlethwaite & Kellaghan, 2009). An alternative view was developed by Dewey (1944, 1991, 1997); he proposed that formal schooling should focus on preparing children and youth to exist in and contribute to a democratic society and that the school should be viewed as a central component of the community where other types of educational experiences could take place. Dewey's central idea was that children and youth should be seen as embedded within a community and society

Hans Rosling (2007, 2010) showed that the traditional rationale for having schools focus on academics is quite clear. Over the last 200 years there has been a dramatic change in lifestyles around the world, with increasing numbers of people moving out of poverty and achieving economic wealth and longer lives. Increased access to schooling and education was a major factor in this change (van der Berg, 2008). However, while this might have served as the primary reason for schooling and education during the 19th and early 20th centuries, it is increasingly apparent that the vision of the good life to which most of humanity aspires (i.e., the lifestyles of the middle class and wealthy in the developed world) is not sustainable nor is it without its shortcomings (Adams, 2006). For example, Rosling shows that the improvement in economic wealth has come at the expense of putting tons of carbon dioxide into the biosphere as a result of burning fossil fuels. Similarly, the World Health Organization (2008) provided data demonstrating that mental health issues, especially depression, are rapidly rising around the world in spite of better economic conditions. The need to develop an approach to schooling and education that both prepares individuals to live successfully in the current context as well as prepare for flourishing in a more sustainable future is just one of the challenges facing educators and societies (MacDonald, 2009; Seligman, 2011; Siedel, 2011; Zimmerman, 2005).

The Importance of Why

As the issues of desired life styles and sustainable ecosystems to create them are debated, there is a need to ask the fundamental question of "Why?" A wide variety of authors and researchers support the importance of asking this question. Sinek (2009) stated that the answer to the "Why?" question is more fundamental than the questions of 'What is to be produced?' or 'How is that going to happen?' Pink (2009) suggested that asking "why" addresses the issue of meaning and purpose of one's actions, one of three primary motivators for adults in the workplace. Seligman (2011) also highlights the importance of meaning and purpose, proposing it as one of the five components of well-being (see Huitt, 2011c, for an overview of Pink's and Seligman's theories). Taken in the context of schooling and education, this suggests that the questions related to why, meaning, and purpose are more fundamental and important than are questions of curricular goals and objectives or methods of instruction and assessment.

One form of the "why" question relates to the issue of the necessity of education, especially the formal education taking place in schools. That is, what is it about the nature of human beings and their potential or lack thereof that requires they be educated, especially in a formal manner? I propose that a perspective incorporating the very beginnings and evolution of the known universe is a necessary, though perhaps not sufficient, condition for understanding human development and behavior. As Spier (2010) states: "the building blocks that are shaping our personal complexity today, as well as the complexity surrounding us, can all be traced back to the emergence and evolution of the universe" (p. 6).

A corollary question is why is the consideration of the "why" question so perplexing at this point in human history. This aspect of the why question is especially important as humanity lives through a period of the most extensive explosion of knowledge and change in its history (Abrams & Primack, 2011; Brown, 2007; Christian, 2011; Spier, 2008, 2010) and is transitioning from an age of competing empires to an age of planetary cooperation (Gilman, 1993, 2014). Kurzweil (2005) provided an excellent overview of the accelerating process of change, making it clear that a whole new range of possibilities is becoming available over which humanity has some potential to control .

Yet another aspect of the "why" question relates to specific alternatives designed to reform current education and schooling practices. For example, although Battle for Kids (2019) created a list of core competencies identifying "the essential skills for success in today’s world," the list omits such factors as getting to know oneself, as well as developing one's emotional and moral character capacities. I believe it is legitimate to ask why certain skills and competencies were included and/or omitted.

The following material provides a very brief overview of some of the latest findings related to how the universe and humanity have evolved to this point. Even though much of this information has been in development for several hundred years, an understanding of the universe as a whole only became available in the latter part of the twentieth century (Primack & Abrams, 2006). I agree with those authors who propose that a scientific understanding of the creation narrative provides the foundation on which to ask further why questions and search for possible alternatives to answer the what and how questions of schooling and education (e.g., Abrams & Primack, 2011; Brown, 2007; Christian, 2011; Spier, 2010). I also agree with those authors who point to the accelerating pace of change and the resulting increased opportunities for individual and sociocultural development that accrue as a result. This essay is not meant to address these issues in detail, but merely to provide educators and non-science-oriented parents an overview to what I believe is an emerging paradigm for developing the capacities of individual human beings as well as a sustainable ecology within which human beings and the biosphere can prosper.

The purpose is to present evidence that there are at least two solid reasons for the importance of formal education or schooling for human beings: (1) develop one's personal innate and inherited potential, and (2) allow one to adapt to, as well as contribute to, the economic and social demands of modern living. And while developing academic competencies are certainly important for economic and social reasons, there are a number of uniquely human capacities that are also important to develop. These potentials are innate in every human being as a result of the complex processes of physical, chemical, and biological evolution. However, the sociocultural milieu of modern life is dramatically different from the conditions in which they developed. These issues are explored further in Huitt (2007) and Huitt (2018).

The next section focuses on current scientific understandings of the physical cosmos and an overview of the development of modern human beings, including the structure and functioning of the brain. However, science is a process of inquiry and investigation that often leads to new data and a reconceptualization or paradigm as new evidence develops (Huitt, 2011b). Some additional research is explored that suggests our current understandings of human beings might need to be modified.

The Big History of the Universe and Humanity

Abrams and Primack (2011) believe that "To act wisely on a global scale, we need to think cosmically" ( p. xv). That is the perspective that will be used to begin to address what it means to be human.

|

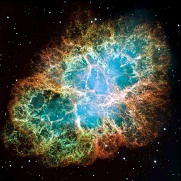

As massive stars consumed their helium, they expanded and then contracted, with the pressure at the center of the dying star forming new chemical elements such as carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen (Abrams & Primack, 2011; Christian, 2011; Greene, 2004). These dead stars then exploded leaving a supernova remnant containing newly created elements. All of the elements, other than hydrogen and helium, used in the creation of the planets, moons, asteroids, etc., as well as the bodies of human beings, were formed in this process. That is, human bodies are created from star dust, as are all other material entities consisting of heavier elements. About 90% of the human body consists of these heavier elements (Primack & Abrams, 2006). |

|

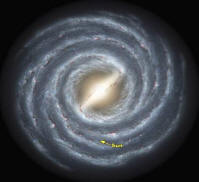

This process is ongoing and has created billions of galaxies and is expected to continue for trillions of years (Abrams & Primack, 2011; Christian, 2011; Greene, 2004). The Milky Way galaxy within which our solar system is located is about 100,000 light years across, but this is relatively small compared to other galaxies. The Andromeda galaxy, which is on a collision course with the Milky Way, is at least twice that size. Do not worry about the collision though as it is not expected to occur for about 4.5 billion years, about the time our sun becomes a red giant. |

|

|

Our solar system was built with the remnants of just such a star-exploding process about 4.6 billion years ago (Abrams & Primack, 2011; Christian, 2011; Greene, 2004). This picture shows the location of our solar system within the Milky Way galaxy. While our solar system is somewhat removed from the center of the galaxy, this isolated location might be a necessary condition for life to have developed on Planet Earth. At the center of the galaxy, there is a lot more celestial activity, such as passing through remnants of dying stars, that might be detrimental to the development of life as it developed on earth. |

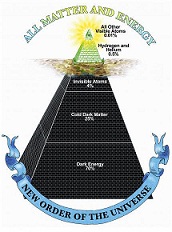

| Astonishingly, only about 0.5% of the universe is visible (i.e., can be observed directly), consisting of hydrogen and helium as well as the heavier elements (Abrams & Primack, 2011; Christian, 2011). Another 4% is comprised of atoms that are thought to exist, but cannot be observed because they are not associated with any form (i.e., they are floating between galaxies). The remainder is cold dark matter (abut 25%) and cold dark energy (about 70%). These are forms of matter and energy that do not reflect light nor give off heat that would make them observable with current instruments. As strange as it might seem, cold dark matter is not atomic (i.e., does not consist of the particles that make up visible matter--protons, electrons, and neutrons; Primack & Abrams, 2006). And cold dark energy is what is causing the universe to expand, rather than contract as might be expected given the force of gravity (Primack & Abrams, 2006). |  |

|

The order of magnitude of the material universe is tremendous, with human beings about in the middle. For example, the total known universe is about 93 billion light years in diameter. Even though the universe is only 13.7 billion years old, the distance from edge to edge is larger than that because it is expanding at an ever-increasing rate. Therefore, scientists cannot see the edge of the universe because it exists further than the time it would take for light from that point in space to reach earth. The average height of a human being is less than 2x102 cm (That is a 2 followed by 2 zeros). The circumference of earth is about 4x108 cm. The size of solar system is about 5.9x1012 cm. The size of Milky Way is about 9x1022 cm. A supercluster of galaxies is about 1025 cm. From earth to the edge of the universe is about 1033 cm (10 followed by 33 zeros). |

Going in the other direction, a molecule is about 10-4 cm (that is a 1 with 4 zeros in front of it -- 0.00001 cm) while an atom is approximately 10-8 cm. This is generally the limit of what can be observed directly with an electron microscope. The nucleus of an atom is approximately 10-13 , much too small to be seen directly. This shrinking in size continues, at least theoretically, to the size of the component of dark matter at approximately 10-25.

|

Life on earth began about 3.5 billion years ago before movement of tectonic plates resulted in the development of the supercontinent Rodinia about 1.1 billion years ago. By the time Rodinia began to fragment about 750 million years ago, complex eukaryotic cells had begun to form. At that time most of the land mass of the earth was in the southern hemisphere. |

| By 200 million years ago, the land mass fragments had come together to form the supercontinent of Pangea; dinosaurs and the first mammals had evolved. The fossil record shows where some of the land masses were connected. Continued land mass movement has resulted in the islands and continents seen today. |  |

|

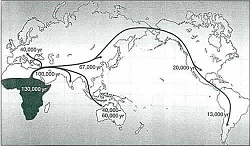

By 200,000 years ago, anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) had evolved in Africa and by 130,000 years ago began to migrate, first to the Middle East, Europe, and Asia, and then on to Australia, and the Americas (Gugilotta, 2008; University of Cambridge, 2007). Presently, there is a consensus that the Americas were the last continents to be settled by human beings between 20,000 to 15,000 years ago, with most researchers supporting a crossing of the Bering Land Bridge from Asia as shown in this map. However, there is a competing view that some people from Europe may have migrated to North America along an Atlantic corridor during that same time period (Bradley & Stanford, 2004). |

The Human Brain

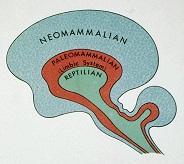

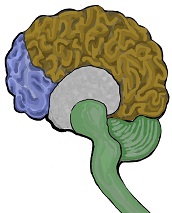

| The process of physical, chemical, and biological evolution that lead to the development of anatomically modern human beings is exemplified in the structure and function of the human brain. MacLean (1970, 1990) proposed that evolutionary processes provided human beings with a brain comprised of three levels -- a triune brain. The first level is the reptilian brain and is composed of the brain stem and the cerebellum. This part of the brain is basically response for behavior intended to keep the organism alive. There is little, if any, learning associated with this part of the brain. The second level is the paleomammalian brain or the limbic system. It is primarily responsible for homeostasis (returning to a set point), emotions, and the processing of short-term memory into long-term memory. The third level is the neomammalian brain or the cortex. It is primarily responsible for long-term memory storage and problem solving. |

|

|

There is growing evidence that a quadrune brain model (Dowd, 2008) better represents the data as the prefrontal cortex, the site of the executive functioning of the brain, continues to develop during adolescence (Steinberg, 2010). This conceptualization of brain structure more clearly overlaps the trilogy of mind theory identified by Hilgard (1980). The limbic system relates to affection, the cortex to cognition, and the prefrontal cortex to conation. |

The development of the paleomammalian brain or limbic system would seem to provide a relatively straightforward foundation for answering the question "Why is education necessary?" At a minimum it points to a number of aptitudes and domains that human beings share with animals such as emotional functioning (Izard, 2009), developing social relationships (Aronson, 2007), and learning from others through modeling (Bandura, 1976). Even this limited list demonstrates that learning and education were important in the animal kingdom before the evolution of modern human beings.

The highly complex and sophisticated human brain provided an ability to engage in a wide range of specifically human abilities such as the use of rational, abstract thought (Piaget, 1972) as well as spoken and written language (Hauser et al., 2002) and a search for meaning or purpose (Seligman, 2011; Wong, 2012). These additional potentials could only be developed in individual human beings through learning and education (Huitt, 2011a). While the biological evolution of human beings continues, cultural evolution has become dominant (Richerson & Boyd, 2005). This ability to change individually and communally, begun in the Paleolithic hunter/gatherer era, extended ever more effectively into the early and later agrarian eras, and continuing into the early and later industrial ages (Huitt, 2007) has allowed human beings to become the most geographically widespread species on the planet (Richerson & Boyd, 2005). Though non-formal (guided teachable moments) and informal (semi-structured, relatively short-term) education was adequate for most of human evolution, it has become necessary for all human beings to participate in formal education (schooling) in order to develop the competencies needed to effectively participate in a modern global society. Simply reviewing statistics on how many adults cannot read or write (Sweet, 1996; World Bank, The, 2011) or engage in abstract symbolic thought (Kuhn et al., 1977) demonstrates this point.

Additional Research and Theory

Three additional bodies of work suggest this is not the end of the story. First, research has demonstrated that humans influence the future through intentional activity (Schwartz & Begley, 2002; Thompson-Schill et al. 2009). Bandura (1986) proposed the capacities that make this possible (intentionality, forethought, self-reactiveness, and self-reflection) differentiate human beings from all other species. Gilbert and Wilson (2007) use the term prospection to describe human beings' abilities to imagine a future and act on it. Seligman et al.(2013) provide additional evidence of these abilities and demonstrate that these can be developed through education. While this might seem to be self-evident given one's personal experiences, a fully determined universe as proposed by Newton and Einstein (Ulanowicz, 2009) would perceive this use of volition or will as an illusion (Bandura, 2001; Haggard, 2008).

The result of these human capacities is that human beings have the potential to contribute to an ever-advancing civilization. That is, using forethought or prospection to imagine a desirable future and developing an action plan to intentionally move towards that end result, human beings can use their self-reactiveness and self-reflection to regulate their thinking and behavior as they progressively move towards an imagined future. Human beings can do more than simply adapt to existing conditions; they can create an environment that they imagine as more desirable. Elgin (2010; Elgin with LeDrew, 1997) proposed this process is currently underway with increasing numbers of people voluntarily adopting a paradigm that can lead to more flourishing lives and more sustainable lifestyles. This adds one more reason to the requirement for formal education, albeit a quite different system than is currently practiced around the world. However, there are formal education programs such as the three International Baccalaureate programs and Walden University's commitment to social change that put this capacity into practice.

Another body of research suggests that the reality of the universe, its structure, functioning, and its development, is much different than what is experienced in our daily routines. For example, it is hypothesized that the smallest sub-particles are strings that vibrate at different frequencies to produce the particles that comprise the material universe (Greene, 2000).

However, knowing that strings vibrate does not lead directly to a proposal of what makes the strings vibrate. It is axiomatic that every effect must have a cause--what is the cause of the string vibration? Deacon (2011) proposed there may never be an answer to that question as current research has yet to empirically identify any fundamental (i.e., non-composite) entities. He suggested, instead, that the universe is comprised of fundamental relationships that are ever-changing in somewhat arbitrary and accidental ways based on probabilities.

Other research in cosmology suggests that the universe is holographic (Smoot, 2010; Talbot, 1991). This hypothesis proposed that "All of the possible histories of the universe, past and future, are encoded on the apparent horizon of the universe" (Smoot, 2010, p. 2249). This two-dimensional informational structure (analogous to the flat surface of a computer disk or a piece of film) has all the information necessary to compute a three-dimensional hologram for all instances of time. One interesting aspect of a piece of holographic film is that any specific piece of the film contains all of the information stored on the complete film. Talbot (1991) suggested an implication of this feature of holographs is that all of the information about the whole universe, past, present, and future, is stored throughout the entire horizon of the universe. Accessing any one piece provides access to the whole.

This research provides yet another reason for formal education for everyone -- developing the ability to explore and understand the nature of reality (ontology) and the nature of knowledge about that reality (epistemology). Human beings are part of the web of life (Capra, 1996), not only on this planet, not only in this universe, but across the cosmos possibly consisting of multiple universes. As part of that web, each individual human being is not only influenced by, but also potentially influences, the cosmos.

One final point. Research has demonstrated that human consciousness continues to exist after the biological body ceases to function (Holden et al., 2009; Lommel, 2010; Long & Perry, 2010; Talbot, 1991). An initial consideration would consider the mind or human consciousness as embedded within the biological brain. However, numerous scientifically-based studies reported that human beings continue to experience conscious thought even though their brains have ceased to function (Holden et al., 2009; Lommel, 2010; Long & Perry, 2010).

There are a variety of hypotheses regarding how this might occur, from radical dualism (body and mind/spirit/soul are composed of different substances) to emergent dualism (mind/soul emerges from the structure and function of the brain and nervous system) to quantum interactive dualism (a dualism based on the interaction of a conscious agent and quantum events) to emergent monism (consciousness/mind/soul are in reality physical properties, but must be studied separately) and many others (Cortez, 2010; Green & Palmer, 2005; Stapp, 2006). However, philosophies such as Churchland's (1981) eliminative materialism or Dennett's (1996) reductive materialism state quite strongly that everything can be reduced to physical explanations and nothing exists outside of those explanations. While there is still much work to be done in this area, those who have adopted a cosmic-spiritual and/or God-centered worldview have much to contribute to this discussion.

Summary and Conclusions

While it is relatively easy to accept that human beings possess a wide range of capacities in multiple domains, other ideas are readily accepted by some and completely denounced as fantasies by others. These include proposals that (1) the material world is always a composite (i.e., there is no single entity or set of fundamental particles), (2) the known universe is only one of many, (3) the physical universe is in realty a holographic image, (4) human beings have the capacity to influence physical reality through intentional behavior, and (5) human consciousness (or mind or spirit or soul) exists separately from the physical body.

However, it should be remembered that many scientific understandings were first discounted before they were accepted. For example, when the concept of an inflationary universe, starting with a specific event later labeled the Big Bang by Fred Hoyle, was first proposed, the accepted model was that of an unchanging universe in line with Newtonian thinking (Lineweaver & Davis, 2005). Leading scientists rejected the big bang theory as recently as the 1960s until irrefutable evidence was provided that the known universe had a specific beginning and is expanding. Many laypeople, as well as scientists, are still confused about the functioning and meaning of this concept (Lineweaver & Davis, 2005). Other examples of twentieth-century ideas that were at first rejected and then accepted include the tectonic plate theory (first proposed by Alfred Wegener in 1915 and denied as late as the 1960s; Glasscoe, 1998) and the probabilistic nature of quantum mechanics (rejected by Albert Einstein, one of its inventors and yet currently accepted as the standard interpretation; Einstein & Infeld, 1938/1966; Schwartz et al., 2005.)

This process of paradigm change in science was described by Kuhn (1962). He showed that scientific practice is dependent upon a scientific paradigm, which he defined as "accepted examples of actual scientific practice, examples which include law, theory, application, and instrumentation together--[that] provide models from which spring particular coherent traditions of scientific research....Men whose research is based on shared paradigms are committed to the same rules and standards for scientific practice" (p. 10). The twentieth century saw a rapid change in paradigms in the natural sciences (Abrams & Primack, 2011; Capra, 1996; Ulanowicz, 2009) as well as the social and behavioral sciences (Elgin with LeDrew, 1997; Nagowah & Nagowah, 2009).

While a consensus seems to be developing around quantum mechanics and dynamical systems in the natural sciences (Abrams & Primack, 2011; Capra, 1996; Ulanowicz, 2009), no such consensus is developing for the social and behavioral sciences, especially applied sciences such as education in all its facets (Huitt, 2011b). If schooling and education are to become more efficient and effective in developing human potential in all its variations as well as preparing people to meet the demands of the twentieth century, developing a paradigmatic consensus is certainly a critical activity (Jordan, 1979). As Primack and Abrams (2006) stated, "Many of humanity's most dangerous problems arise from our seventeenth-century way of looking at the universe, which is at odds with the principles of science that we blithely use in countless technologies" (p. 4).

This article has been an essentially top-down approach to investigating human potential. The next article in the series will address the same issue from a bottom-up approach, looking at the investigations of specific aptitudes and abilities that researchers have labeled as intelligences (Huitt, 2011a).

References

Abrams, N., & Primack, J. (2011). The new universe and the human future: How a shared cosmology could transform the world. Yale University Press. (See http://new-universe.org/TerryLectures.html)

Adams, W. M. (2006). The future of sustainability: Re-thinking environment and development in the twenty-first century. The World Conservation Union IIUCN). Retrieved from http://cmsdata.iucn.org/downloads/iucn_future_of_sustanability.pdf

Aronson, E. (2007). The social animal (10th ed.). Worth Publishers.

Bandura, A. (1976). Social learning theory. Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 1-26. http://www.des.emory.edu/mfp/Bandura2001ARPr.pdf

Battle For Kids (2019). P21 framework definitions. Author. https://www.battelleforkids.org/networks/p21/frameworks-resources

Bradley, B., & Stanford, D. (2004). The North Atlantic ice-edge corridor: A possible Palaeolithic route to the New World. 36(4), 459-478. http://planet.uwc.ac.za/nisl/Conservation%20Biology/Karen%20PDF/Clovis/Bradley%20&%20Stanford%202004.pdf

Brown, C. S. (2007). Big history: From the big bang to the present. W. W. Norton.

Capra, F. (1996). The web of life: A new scientific understanding of living systems. Anchor Books, Doubleday.

Christian, D. (2011). Maps of time: An introduction to big history. University of California Press.

Churchland, P. (1981). Eliminative materialism and the propositional attitudes. The Journal of Philosophy, 78(2), 67-90. https://doi.org/10.2307/2025900

Cortez, M. (2010). Theological anthropology: A guide for the perplexed. T&T Clark International.

Deacon, T. (2011). Incomplete nature: How mind emerged from matter. W. W. Norton.

Dennett, D. (1996). Facing backwards on the problem of consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 3(1), 4-6. https://personal.lse.ac.uk/ROBERT49/teaching/ph103/pdf/dennett1996.pdf

Dewey, J. (1944). Democracy and education. Macmillan. http://www.ilt.columbia.edu/publications/dewey.html [Originally published in 1916].

Dewey, J. (1991). School and society and The child and the curriculum (Reissue edition).

Dewey, J. (1997). Experience and education. Macmillan. [Originally published in 1938].

Dowd, M. (2008). Thank God for evolution: How the marriage of science and religion will transform your life and our world. Plume/Penguin.

Einstein, A., & Infeld, L. (1938/1966). The evolution of physics: From early conceptions to relativity and quanta. Simon & Schuster.

Elgin, D. (2010). Voluntary simplicity: Toward a way of life that is outwardly simple, inwardly rich (2nd ed.). Harper.

Elgin, D. with LeDrew, C. (1997). Global consciousness change: Indicators of an emerging paradigm. Millenium Project. http://www.duaneelgin.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/global_consciousness.pdf

Gilbert, D., & Wilson, T. (2007). Prospection: Experiencing the future. Science, 317(5843), 1351-1354. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1144161

Gilman, R. (1993, Fall). What time is it? Finding our place in history. In Context, 36. http://www.context.org/iclib/ic36/gilman1/

Gilman, R. (2014, February 12). What time is it? Foundation Stone 1. http://www.context.org/foundation-stones/what-time-is-it/wtii-videos/

Glasscoe, M. (1998). The history of plate tectonics. The Southern California Integrated GPS Network (SCIGN) Education Module. http://scign.jpl.nasa.gov/learn/plate2.htm

Green, J., & Palmer, S. (Eds.). (2005). In search of the soul: Four views of the mind-body problem. InterVarsity Press.

Greene, B. (2000). The elegant universe: Superstrings, hidden dimensions, and the quest for the ultimate theory. W. W. Norton.

Greene, B. (2004). The fabric of the cosmos: Space, time, and the texture of reality. Knopf.

Gugliotta, G. (2008). The great human migration. Smithsonian. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history-archaeology/human-migration.html

Haggard, P. (2008). Human volition: Towards a neuroscience of will. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9(12), 934-946. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2497

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

Hauser, M., Chomsky, N., & Fitch, W. T. (2002, November 22). The faculty of language: What is it, who has it, and how did it evolve? Science, 298, 1569–1579. http://www.chomsky.info/articles/20021122.pdf

Hilgard, E. (1980). The trilogy of mind: Cognition, affection, and conation. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 16(1), 107-117. https://eli.johogo.com/Class/trilogy-1980.pdf

Holden, J., Greyson, B., & James, D. (Eds). (2009). The handbook of near-death experiences: Thirty years of investigation. ABC-CLIO, LLC.

Huitt, W. (2007). Success in the Conceptual Age: Another paradigm shift. Paper delivered at the 32nd Annual Meeting of the Georgia Educational Research Association, Savannah, GA, October 26. http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/papers/conceptual-age.pdf

Huitt, W. (2011b). Analyzing paradigms used in education and schooling. Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta State University. http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/topics/intro/paradigm.pdf

Huitt, W. (2011c). Motivation to learn: An overview. Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta State University. http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/topics/motivation/motivate.html

Huitt, W. (2012). A systems approach to the study of human behavior. Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta State University. http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/materials/sysmdlo.html

Huitt, W. (2018a). The Brilliant Star framework. In W. Huitt (Ed.), Becoming a Brilliant Star: Twelve core ideas supporting holistic education (pp. 5-23). IngramSpark, http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/papers/2018-01-huitt-brilliant-star-framework.pdf

Huitt, W. (2018b). Understanding reality: The importance of mental representations. In W. Huitt (Ed.), Becoming a Brilliant Star: Twelve core ideas supporting holistic education (pp. 65-81). IngramSpark. http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/papers/2018-04-huitt-brilliant-star-representations.pdf

Izard, C. (2009). Emotion theory and research: Highlights, unanswered questions, and emerging issues. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 1-25. http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/pdf/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163539

Jakobi, A., & Teltemann, J. (2011). Convergence in education policy? A quantitative analysis of policy change and stability in OECD countries. Compare: A Journal of Comparative & International Education, 41(5), 579-595. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2011.566442

Jordan, D. (1979). Rx for Piaget's complaint. Journal of Teacher Education, 30(5), 11-14. http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/anisa/overview/Rx_for_Piaget.html

Kuhn, T. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. University of Chicago Press. [see study guide at http://www.emory.edu/EDUCATION/mfp/Kuhn.html]

Lineweaver, C., & Davis, T. (2005). Misconceptions about the Big Bang. Scientific American, 292(3), 36-45. http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=misconceptions-about-the-2005-03

Lommel, P. van. (2010). Consciousness beyond life: The science of the near-death experience. [Trans. Laura Vroomen]. HarperCollins.

Long, J, with Perry, P. (2010). Evidence of the afterlife: The science of near-death experiences. HarperCollins.

Kuhn, D., Langer, J., Kohlberg, L., & Haan, N. S. (1977). The development of formal operations in logical and moral judgment. Genetic Psychology Monographs, 95, 97-188. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1977-27210-001

Kurzweil, R. (2005, February). How technology's accelerating power will transform us. http://www.ted.com/index.php/talks/view/id/38

MacLean, P. (1970). The triune brain, emotion, and scientific bias. In F. Schmitt (Ed.), The neurosciences: Second study program (pp. 336-349). The Rockefeller University Press.

MacLean, P. (1990). The triune brain in evolution: Role in paleocerebral functions. Springer.

MacDonald, J. (2009). Balancing priorities and measuring success: A triple bottom line framework for international school leaders. Journal of Research in International Education, 8(1), 81-98. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240908100682

Nagowah, L., & Nagowah, S. (2009). A reflection on the dominant learning theories: Behaviourism, cognitivism and constructivism. International Journal of Learning, 16(2), 279–285. https://doi.org/10.18848/1447-9494/CGP/v16i02/46136Piaget, J. (1972). Intellectual evolution from adolescence to adulthood. Human Development, 15(1), 1-12.

Pink, D. (2009). Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us. Riverhead Books.

Postlethwaite, T. N., & Kellaghan, T. (2009). National assessments of educational achievement. Paris, France, Brussels, Belgium: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), International Academy of Education, International Institute for Educational Planning. http://www.iiep.unesco.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Info_Services_Publications/pdf/2009/EdPol9.pdf

Primack, J., & Abrams, N. (2006). The view from the center of the universe: Discovering our extraordinary place in the cosmos. Riverhead Hardcover.

Richerson, P., & Boyd, R. (2005). Not by genes alone: How culture transformed human evolution. University of Chicago Press.

Rogers, C., & Freiberg, H. J. (1994). Freedom to learn (3rd ed.). Macmillan/Merrill.

Rosling, H. (2007). New insights on poverty. Presentation at TED conference, March. https://www.ted.com/talks/hans_rosling_new_insights_on_poverty

Rosling, H. (2010): The magic washing machine. Presentation at TED conference, December. https://www.ted.com/talks/hans_rosling_the_magic_washing_machine

Schwartz, J., & Begley, S. (2002). The mind and the brain: Neuroplasticity and the power of mental force. HarperCollins.

Schwartz, J., Stapp, H., & Beauregard, M. (2005). Quantum theory in neuroscience and psychology: A neurophysical model of mind/brain interaction. Phil. Trans. Royal Society, B 360(1458), 1309-1327. http://www-physics.lbl.gov/~stapp/PTRS.pdf

Seligman, M. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press.

Seligman, M., Railton, P., Baumeister, R., Sripada, C. (2013). Navigating into the future or driven by the past. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(2), 119-141. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612474317

Siedel, P. (2011). To achieve sustainability. World Futures, 67(1), 22-29. https://doi.org/10.1080/02604027.2010.532466

Sinek, S. (2009). Start with why: How great leaders inspire everyone to take action. Portfolio/Penguin.

Smith, M. S., & Day, J. (1990). Systemic school reform. In S. Fuhrman & B. Malen (Eds.), Politics of Education Association yearbook (pp. 233-267). Taylor & Francis.

Smoot, G. (2010). Go with the flow, average holographic universe. International Journal of Modern Physics D, 19(4), 2247-2258. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1003.5952

Spier, F. (2008). Big history: The emergence of an interdisciplinary science? Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, 33(2), 141-152. http://worldhistoryconnected.press.illinois.edu/6.3/spier.html

Spier, F. (2010). Big history and the future of humanity. Wiley-Blackwell.

Squires, D., Huitt, W., & Segars, J. (1982). Effective classrooms and schools: A research-based perspective. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Steinberg, L. (2010). A behavioral scientist looks at the science of adolescent brain development. Brain and Cognition, 72(1), 160-164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2009.11.003

Sweet, R., Jr. (1996). Illiteracy: An incurable disease or education malpractice? The National Right to Read Foundation. http://www.nrrf.org/essay_Illiteracy.html

Stapp, H. (2006). Quantum interactive dualism: An alternative to materialism. Journal of Consciousness. Studies, 12(11), 43-58. (Reprinted in Zygon 41, #2 September 2006. 599-615.) http://www-physics.lbl.gov/~stapp/QID.pdf

Talbot, M. (1991). The holographic universe. HarperCollins.

Thomspon-Schill, S., Ramsear, M., & Chrysikou, E. (2009). Cognition without control: When a little frontal lobe goes a long way. Current Directions in Psychological Research, 18(5), 259-263. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01648.x

Ulanowicz, R. (2009). A third window: Natural life beyond Newton and Darwin. Templeton University Press.

University Of Cambridge (2007, May 9). New research confirms 'Out of Africa' theory of human evolution. ScienceDaily. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/05/070509161829.htm

van der Berg, S. (2008). Poverty and education. France & Belgium: The International Institute for Education Planning (IIEP), The International Academy of Education (IAE). http://www.iiep.unesco.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Info_Services_Publications/pdf/2009/EdPol10.pdf

Wong, P. (Ed.). (2012). The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications. Routledge.

World Bank, The. (2011). Literacy rate, adult total (% of people ages 15 and above). http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.ADT.LITR.ZS

World Health Organization. (2008). Investing in mental health. http://www.who.int/mental_health/en/investing_in_mnh_final.pdf

Zimmerman, (2005). Integral ecology: A perspectival, developmental, and coordinating approach. World Futures, 61(3), 50-62. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02604020590902353

Return to: | Brilliant Star Framework | Home Page |

All materials on this website [http://www.edpsycinteractive.org] are, unless otherwise stated, the property of William G. Huitt. Copyright and other intellectual property laws protect these materials. Reproduction or retransmission of the materials, in whole or in part, in any manner, without the prior written consent of the copyright holder, is a violation of copyright law.