Analyzing Paradigms Used in Education and Schooling

Citation: Huitt, W. (2020). Analyzing paradigms used in education and schooling. Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta State University. http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/topics/intro/paradigm.html

A paradigm may be thought of as a mental representation of how an entity is structured (the parts and their interrelationships) and how it functions (behavior within a specific context or time dimension) (Huitt, 2018c). Kuhn (1962) defined a scientific paradigm as "accepted examples of actual scientific practice, examples which include law, theory, application, and instrumentation together--[that] provide models from which spring particular coherent traditions of scientific research....Men whose research is based on shared paradigms are committed to the same rules and standards for scientific practice" (p. 10). By extension, an educational paradigm would describe particular practices and methods and define how theory and research should be used in this practice.

Both Harmon (1970) and Baker (1992) built on Kuhn's definition. Harmon defined a paradigm as "the basic way of perceiving, thinking, valuing, and doing associated with a particular vision of reality..." (p. 5), while Baker defined it as "a set of rules and regulations (written or unwritten) that does two things: (1) it establishes or defines boundaries; and (2) it tells you how to behave inside those boundaries in order to be successful. Finally, Capra (1996), working from a dynamic systems perspective, defined a paradigm as "a constellation of concepts, values, perceptions and practices shared by a community, which forms a particular vision of reality that is the basis of the way a community organizes itself" (p. 6). Each of these definitions can be applied to the practice of education in all of its forms (Fordam, 1993).

Individuals have paradigms that cover many aspects of life such as what kind of car to buy or what kind of food to eat. One of the most important paradigms, however, is one's worldview, a set of constructed perceptions and ideas about how the world works. According to Aerts et al. (1994), a worldview is a "coherent collection of concepts and theorems that must allow us to construct a global image of the world, and in this way to understand as many elements of our experience as possible." This mental representation provides a frame of reference that guides one's understanding of reality and establishes the foundation by which one gives meaning to experiences and thoughts. These are heavily influenced by the culture within which one lives and a person's earliest experiences within a family and community.

To the extent that one's worldview and paradigm are valid or true, they can be used to successfully navigate through the challenges and obstacles of one's personal and professional life. To the extent that these are inaccurate, individuals may make decisions and choices that will ultimately bring results that are unwanted or unintended. As educators and parents, it is therefore essential that adults spend time developing a valid worldview and paradigm that can be taught to students and children as they prepare for successful adulthood.

A major problem in establishing a correct or valid paradigm of reality consists of two aspects. First, while there is possibly an objective reality to be investigated, each individual does so through the subjective reality of one's personal understandings, as influenced by one's immersion in a physical, social, and cultural context (Hatcher, 1990).

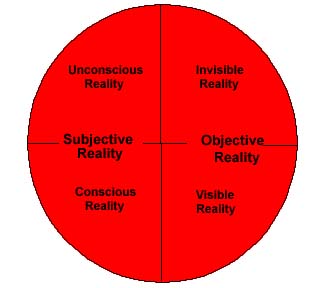

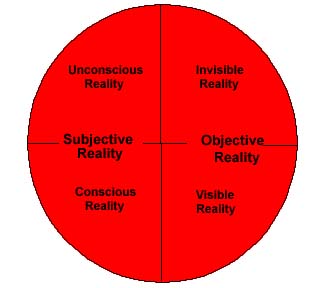

Hatcher depicts this dilemma as shown in Figure 1. From this perspective, there are four categories of reality and descriptions of how reality is structured and works. First, there is an objective reality that has two components: invisible and visible. The visible, objective reality is the one observed by animals and the stated focus of 18th and 19th century science (Newton, 2010). The invisible, objective reality exists, but is not readily observable. One of the great contributions of science is the development of an increasing array of technologies such as microscopes, telescopes, x-ray, and MRI equipment that allow what was previously invisible to become more visible. The subjective reality has become the focus of post-modern thought and is heavily influenced by quantum theories in physics as well as existential and phenomenological philosophies (Schwartz & Begley, 2003). The subjective, conscious reality refers to what we think we know explicitly about reality and has been the focus of cognitive psychology (Bruner, 1977; Neisser, 1967). Studies in neuroscience on subjective, unconscious reality have demonstrated that the phenomenon discussed in ancient philosophy and modernized by Freud and Jung has a basis in brain activity (Imbasciati, 2020).

Figure 1. The Basic Categories of Existence

Second, the combination of one's worldview and paradigm, as constructs of one's perceived reality, focuses attention on certain aspects of objective reality and guides one's interpretation of the possible structure and functioning of both visible and invisible reality (Thulasidas, 2008). It also guides one's understanding and interpretation of the unconscious aspect of subjective reality. It is therefore absolutely critical that a person's, as well as a society's and culture's, subjective interpretations match objective reality. The paradigms educators and parents use to define desired outcomes for students and children influence decisions such as selecting curriculum, defining appropriate teaching methods, and measuring progress. To the extent these paradigms are incorrect, children and youth may be making significant progress in school, while being unprepared for the opportunities and challenges that await them as adults.

As an analogy, one may desire to drive from one city to another. The car is carefully checked, there is plenty of gas, and the drive is started. There is little traffic and it is possible to travel the legal speed limit on a major highway. However, if the road does not go to the desired destination, the person will never arrive there. Likewise, if educators have established desired outcomes, established criteria, and designed appropriate teaching methods and indicators of progress, they may still not be assisting students to become successful adults. It is possible that paradigm used to create the desired outcomes leads to the selection of different goals and objectives than those actually needed for success in a particular location or time frame. Parents and educators need to pay close attention to important trends (Huitt, 2017) and domains of human potential (Huitt, 2018a) and do the best they can to imagine what the world will be like in 5, 10, 15 or even 25 years. Adults responsible for the education of young people need to constantly reevaluate whether the stated desired outcomes are correct and constantly adjust curriculum and teaching methods.

In many ways, educational psychology is an analysis of competing mental representations about the practices of teaching and learning. One of the goals of the study of educational psychology is that practitioners will develop a more explicit, conscious, and visible statement of his or her worldview and paradigm that can be used systematically to guide teaching practice. The two dominant classroom practice paradigms used today are instructivism or teacher-centered classroom practice (Huitt, Monetti, & Hummel, 2009) and constructivism or learner-centered classroom practice (Jonasssen, 1999). Each of these is supported by a set of theories that are central to educational psychology, has a particular view for describing learners, and advocates a particular role for teachers’ classroom practice (See table 1).

As different worldviews and paradigms are explored, practitioners begin to develop a framework that presents an understanding of human growth and development based on theories and research. This provides the foundation for theories of pedagogy (how to guide learning for children and youth) and andragogy (how to guide learning for adults) as well as theories of curriculum and assessment. These, in turn, influence thinking about how learning environments should be organized and relate to other social institutions, the actual practices taking place in nonformal, in-formal, and formal learning situations (Fordam, 1993), and methods for evaluating learning and communicating results with interested stakeholders. And, of course, as all of these are reciprocally connected, the influences are constantly going back and forth. The most common frameworks used in education today include factors in the following categories:

- Context--factors included in domains such as sociocultural, community, family, neighborhood, or school).

- Input--factors that describe teacher and student characteristics before they enter the teaching-learning experience

- Process—factors that describe teacher and students thinking, feeling, planning, and behavior while engaged in learning activities.

- Output—factors that describe assessments of learning at the end of the learning experience.

Table 1. Paradigms, Theories, and Practices

|

Classroom Practice Paradigm

|

Learning Theory

|

View of the Learner

|

Task of the Teacher

|

|

Instructivism (Teacher-centered)

|

Behaviorism/ Operant Conditioning

|

Reactive adaptor

|

Arrange the correct environment and provide the appropriate stimuli after the target behavior has been emitted.

|

|

Information Processing

|

Processor of information

|

Provide opportunities for learners to cognitively process information so learners engage in attention, repetition, and elaboration of target knowledge.

|

|

Social Learning

|

Observer reactor

|

Model desired processes and skills and then use operant conditioning to modify those to the desired standard.

|

|

Constructivism (Learner-centered)

|

Social Constructivism

|

Apprentice

|

Model desired processes and skills and provide assistance to help practice the target knowledge or skill; selectively withdraw the assistance until the learner can demonstrate mastery independently.

|

|

Cognitive Constructivism

|

Inquirer

|

Arrange the environment is such a way that independent and collective investigation can occur relatively unheeded by outside interference.

|

|

Humanistic

|

Autonomous agent

|

Assist the learner to develop an understanding of personal interests and goals and facilitate the development of personally-important capacities.

|

|

Social Cognition

|

Embedded agent

|

Facilitate the learner to adapt to socially-prescribed requirements as well as to establish personal learning goals; facilitate the development of the knowledge, attitudes and skills necessary for meta-cognitive and self-regulation as the learner works to successfully master both sets of goals.

|

|

Connectivism

|

Networked life-long learner

|

Assist the learner to connect to various networks of knowers, inquirers, and knowledgebases; empower learners to be producers of knowledge that can be accessed throughout one's lifetime.

|

A practical, realistic approach to reforming actual practice starts with a society or educational institution defining desired target behaviors. At present, the focus is on basic academic or essential knowledge and skills for a particular task, but this is proving insufficient for the digital, global, fast-paced sociocultural environment seen today (Huitt, 2018b). There is then a need to devise an approach to assessment, measurement, and evaluation instruments and procedures used to verify that learning has occurred; these put one's educational paradigm into practice as it is the methods of accountability that actually drive curriculum and instructional practices (e.g., Hummel & Huitt, 1994). When assessment practices do not match the curriculum-design targets, it can result in disconnections or a lack of coherence among the different components in the framework, resulting in a fractured, inefficient, and ineffective approach to schooling.

The reading materials for the course will concentrate on research and understandings developed using social and behavioral science methodology. As part of the process of making one's worldview, paradigm, and framework of teaching and learning more explicit, you are encouraged to consider the following questions:

- Based on what you know about human development, what are the most important desired targets for learning in the environment in which you want to teach?

- Based on what you know about assessment, measurement, and evaluation, what are some ways that learning and development related to these targets might be assessed?

- Based on what you know about learning, what is your opinion on the different views of the learner as described in table 1? That is, which most closely match your current understandings?

- Based on what you know about classroom practice, what is your view of the roles of the teacher advocated by the different paradigms and theories?

- When you inquire about best classroom or teaching-learning practices, what are some search terms you would use to guide your inquiry?

It is not expected that every learner will have a fully-developed worldview, paradigm, and framework at the end of the course. However, it is expected that everyone will have considered the competing alternatives and will be better prepared to construct and evaluate approaches to teaching and learning that can be used in a variety of situations, incorporating appropriate methods, strategies, and practices advocated in current professional practice.

References

Aerts, D., Apostel, L., De Moor, B., Hellemans, S., Maex. E., Van Belle, H., Van Der Veken, J. (1994). Worldviews: From fragmentation to integration. VUB Press. http://pespmc1.vub.ac.be/CLEA/Reports/WorldviewsBook.html

Baker, J. (1992). Paradigms: The business of discovering the future. HarperBusiness.

Bruner, J. (1977). A study of thinking. Krieger Publishing.

Capra, F. (1996). The web of life: A new scientific understanding of living systems. Anchor Books.

Fordham, P. (1993). Informal, non-formal and formal education programmes in YMCA. In P. Fordham, ICE301: Lifelong learning, Unit 1 Approaching lifelong learning. George Williams College. http://infed.org/mobi/informal-non-formal-and-formal-education-programmes/

Hatcher, W. (1990). Logic and logos: Essays on science religion, and philosophy. George Ronald Press.

Huitt, W. (2017). A phase change: Forces, trends, and themes in the human sociocultural milieu. Valdosta State University. http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/papers/2017-huitt-a-phase-change.pdf

Huitt, W. (2018a). The Brilliant Star framework. In W. Huitt (Ed.), Becoming a Brilliant Star: Twelve core ideas supporting holistic education (pp. 5-23). IngramSpark. http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/papers/2018-01-huitt-brilliant-star-framework.pdf

Huitt, W. (2018b, January). Phasing-in: Exploring necessary capacities and implications for success in the next three decades. Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta State University. http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/papers/2018-huitt-phasing-in-exploring-necessary-capacities-rev.pdf

Huitt, W. (2018c). Understanding reality: The importance of mental representations. In W. Huitt (Ed.), Becoming a Brilliant Star: Twelve core ideas supporting holistic education (pp. 65-81). IngramSpark. http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/papers/2018-04-huitt-brilliant-star-representations.pdf

Huitt, W., Monetti, D., & Hummel, J. (2009). Designing direct instruction. In C. Reigeluth and A. Carr-Chellman, Instructional-Design Theories and Models: Volume III, Building a Common Knowledgebase (pp. 73-97). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/papers/designing-direct-instruction.pdf

Hummel, J., & Huitt, W. (1994, February). What you measure is what you get. GaASCD Newsletter: The Reporter, 10-11. http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/papers/wymiwyg.pdf

Imbasciati, A. (2020). The unconscious and consciousness of the memory: A contribution from neuroscience. International Forum of Psychoanalysis, 29(2), 115–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/0803706X.2020.1711966

Jonasssen, D. (1999). Designing constructivist learning environments. In C. Reigeluth (Ed.), Instructional-design theories and models. Volume II. A new paradigm of instructional theory. (pp. 215-239). Erlbaum.

Jordan, D. (1974). A summary statement of the ANISA model. ANISA. https://www.edpsycinteractive.org/anisa/overview/summary_ANISA.pdf

Kuhn, T. (1970). The structure of scientific revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

May, T. (2001). Our practices, our selves, or what it means to be human. The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Neisser, E. (1967). Cognitive psychology. Appleton-Century-Crofts

Newton, I. (2010). The principia: Mathematical principles of natural philosophy (3rd ed.). Snowball Publishing. (Originally published in 1726).

Schwartz, J., & Begley, S. (2003). The mind and the brain: Neuroplasticity and the power of mental force. Harper Perennial.

Thulasidas, M. (2008). Perception, physics, and the role of light in philosophy. The Philosopher, 96(1). https://www.thulasidas.com/perception-physics-and-the-role-of-light-in-philosophy/

Return to:

· Return to Science: A Way of Knowing

· EdPsyc Interactive: Courses

· Home Page

All materials on this website [http://www.edpsycinteractive.org] are, unless otherwise stated, the property of William G. Huitt. Copyright and other intellectual property laws protect these materials. Reproduction or retransmission of the materials, in whole or in part, in any manner, without the prior written consent of the copyright holder, is a violation of copyright law.